Using social networks to help migrants, an original project by a Berlin association

With the support of the European Union, the German NGO Minor uses Facebook, Telegram and TikTok to identify migrants in need, answer their sometimes urgent questions and support them in their integration process.

At its core, the Internet was supposed to be a network in all senses of the word: a decentralised place of equality and connection, showing us that we are all linked to each other globally. However, our digital spaces have mutated significantly from the utopian ideals of the World Wide Web at its founding. Doom scrolling leads us to more anxiety and depression. To drive online engagement, social media platform algorithms capitalize on extreme emotions such as anger. Algorithms isolate and divide users on (political) topics, and filter bubbles lead to increasing hatred and polarization.

Despite our growing awareness about the negative effects of social media, society is currently building on it. Traditional media is declining, companies are rushing to platforms like Instagram and TikTok to promote their services or products, and in our youngest generation, for about one-third it is their dream job to be a ‘YouTuber’. From figuring out where to eat tonight, telling your friends about your last date, or logging into work with an authenticator: we need our little pocket screens to function in the wild world. But these are not the only indicators that define the scope of our network-reliance. For refugee and immigrant communities, using social media has become a matter of life and death.

The essence of smartphones for refugee and migrant communities first came to light during the start of the Syrian refugee crisis in 2015. Refugees used their phones to stay in touch with loved ones through apps like Whatsapp and Facebook Messenger, to navigate, and to follow the news. Phones and powerbanks became a basic human need, according to some refugees even more important than food.

Main source of information

This crucial reliance on social media for communities in need is present more than ever today. For Ukrainian refugees in Germany, social media is their main source of information. This includes staying up to date on the development regarding the war, but also to acquire more information about the host country.

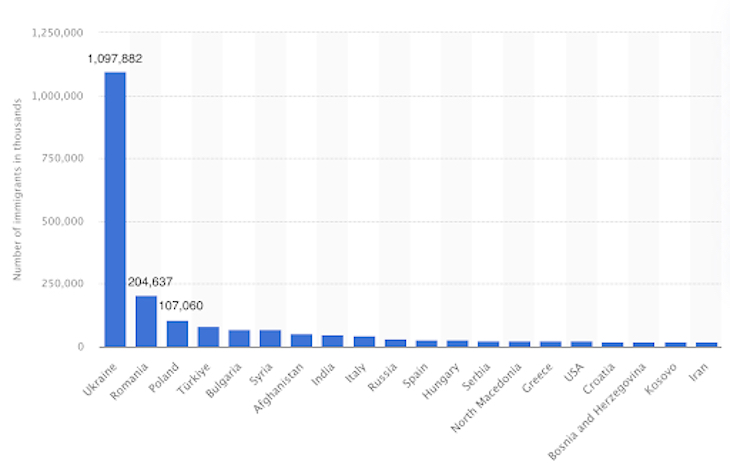

The struggle of building a life does not come to an end once refugees and immigrants have arrived in a country: on the contrary, it has only just begun. For many, a long process of integration[1] lies ahead. And in Europe, the largest bulk of these people are in Germany. Not only is it the biggest economy (measured in GDP) and the largest population in the EU, but Germany also receives the largest number of immigrants on a yearly basis.

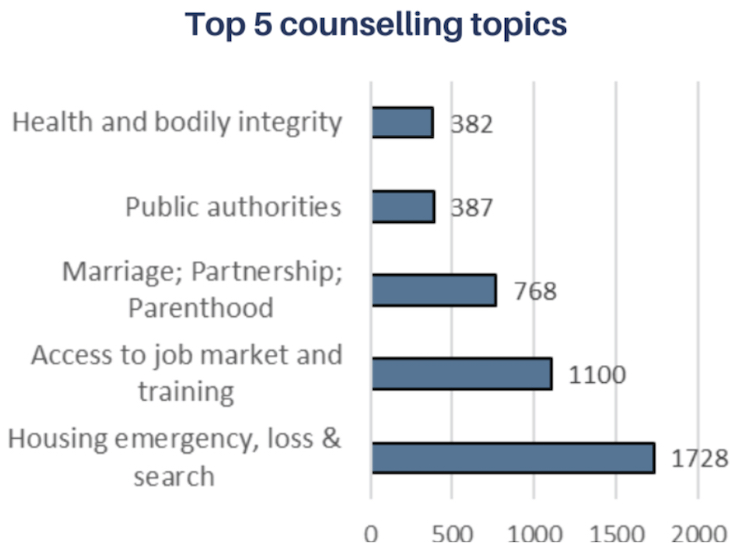

For the long and winding road of integration in Germany, basic needs such as housing and food of course need to be met first. Building on to that, newcomers struggle with finding jobs, education for their children, and overall understanding how the system of their host country works. Language barriers play a huge role in this process: how would you know how to apply for healthcare and register for your GP, if you cannot speak German? How do you register your child for a new school? How do you even find a house, with the current housing crisis that’s going on in Europe? How do you deal with discriminatory remarks from your neighbor? You may have guessed it – for many, this means you go on social media.

One organization that understood this perfectly is Minor – Projektkontor für Bildung und Forschung (“Project Office for Education and Research”). Minor is a civil society actor based in Berlin that works on a variety of projects related to strengthening democracy and social cohesion, with a strong focus on migration.

What’s unique about the organization is their principle of migrant-to-migrant support: many employees have a family history of migration or are migrants themselves. Because of this, the organization can have a comprehensive understanding of what migrant and refugee communities need; the staff is not just supporting the communities, they are a part of it.

Minor’s team realized the importance of social media in the integration processes in their host country Germany. They founded two projects aimed at incorporating these services and using social media as a tool for assistance, both funded by German authorities and the European Social Fund+ (ESF+). These projects are named ‘Social Media Street Work’ (SoMS) and ‘Social Media Bridge’ (SoMB). SoMS focuses on immigrants in Germany from EU countries, whilst Social Media Bridge SoMB supports refugees. The projects launched in 2022 and aim at integrating “those on the fringes of society into the mainstream” by reaching out to newcomers on social media platforms.

Social media Street work

For SoMS, the team consists of 6 people and 7 working languages: German, Polish, Romanian, Bulgarian, Croatian, English and Italian – these languages encompass the largest migrant groups of EU citizens in Germany.

Staff at the SoMB project speak Arabic, English, French, Kurdish, Persian, Russian, Turkish and Ukrainian.

Cooperation between the two projects is narrow: the teams share an office space together, and frequently have meetings to share experiences and knowledge. In terms of the work they do, the projects share the same systematic strategy to find relevant questions online.

Firstly, they identify where an immigrant community is most active. Not all target groups use all the same platforms and spaces, it depends on the community. Most refugee and migrant communities use (closed) Facebook groups which are set up by the refugee communities themselves, but Telegram is the primary platform used by Ukrainians, so this is where the staff member covering the Ukrainian language will be most active. On the platforms, the team uses buzzwords to find the relevant online spaces and joins them with the organization’s account. Then, within these spaces, SoMS and SoMB staff spend their time browsing for unanswered or incorrectly answered questions that have to do with the integration process.

This approach has upsides and downsides. On the one hand, trolls are everywhere on the internet – even in closed, small spaces. Sabina, a staff member focused on Croatian and English speaking communities, recalls: “it’s different when you work with people in real life. There will always be one person who disagrees with what you write. They ask themselves, “who is this person anyway?” There is a lot of suspicion in social networks.”

Answering migrants’ questions

This is understandable – the concept and approach that Minor is using is very new, and especially with the often-concerning developments surrounding social media, it is not surprising that people are distrusting of social media initiatives.

However, a lot of people rely on these spaces, sometimes with their whole lives. Sabina continues: “I had a domestic violence case, where a woman wrote me asking what she should do. I told her to call the police and provided her with the contacts of safe houses and hotlines for women victims of domestic violence.” A significant cultural difference between the Balkans and Germany is trust in the role of the police – in this case, Sabina assured the woman that the police would respond to the situation. “She went to court the next day and kept me updated on her situation and the challenges she faced. I, along with other ladies in the group, continuously wrote to her, offering encouragement and reminding her that she was not alone.” This shows that although for most of us social media is a form of entertainment, and its structures are in many ways polluted and toxic for our wellbeing, some online spaces still uphold values of connection, and people rely on it for their lives. For women like the woman in Sabina’s story, sometimes these spaces are their only form of support. It is pivotal that actors like Minor can incorporate the use of social media spaces in their services.

SoMS and SoMB do not just offer online consulting services– they also work as a referral service. Both are part of a wider network of services working to support refugees and immigrants in Germany. SoMS is part of EhAP Plus, a network of projects funded by the ESF+ and German Ministry of Labour and Social Affairs and co-financed by the the EU Equal Treatment Office at the Federal Government Commissioner for Migration, Refugees and Integration. Other projects in the network consist of o.a. advisory and counselling in person in smaller communities throughout the country. SoMS staff also teamed up with BAG Wohnungslosenhilfe e.V, an iniative focused on fighting homelessness and supporting homeless people or people at risk of becoming homeless. SoMB is a part of WIR, a network to help integrate refugees in the regional labour market[SF1] in line with their qualifications. The model project “Social Media Bridge” is part of the project “bridge – Berline Netzwerk für Bleiberecht”

The project “bridge – Berlin Network for the Right to Stay” is funded by the Federal Ministry of Labour and Social Affairs and the European Union through the European Social Fund Plus (ESF Plus) as part of the programme “WIR – Networks Integrate Refugees into the Regional Labour Market” and co-funded by the state of Berlin (Berliner Landesmittel). Whenever a person includes their location in their online question, SoMB and SoMS inform them of the local, in-person resources available to them. And, where people do not have access to local services, SoMB and SoMS provide the digital alternatives to fill the gap, leveraging the growing reliance on our digital lives to support those who need it most in the real world.

A difficult challenge for Minor’s projects is the reach they have. The people they help are the ones already a part of online communities, who know where to go to on social media to get support from others. This leaves out members of the community who may struggle to find these networks. This is why the projects are currently working hard to build a name on the existing social media platforms. Additionally, in a consultation with other social organizations in Berlin, the team at Minor came to the realization that for those who need that extra hand most, many are analphabetic, and therefore even less likely to find their safety net online, where written posts are the main currency. Therefore, Minor is currently experimenting with TikTok as an additional platform for outreach. The idea is to create videos with useful information, such as applying for unemployment or childcare benefits, for the new arrivals in Germany. As social media keeps evolving, civil society actors like Minor should be able to keep innovating with it.

Minor kontor’s ESF+ funded projects acknowledge how, for better or worse, social media has become essential in the integration process, and uses it for positive ends instead of negative ones. Additionally, the projects refer those in need to in-person services where necessary, also showing the importance of real-life support and connection. The Internet and social media are here to stay, and with initiatives like these, we can leverage innovative solutions for positive change.

[SF1]Between these two sentences, please add this: The model project “Social Media Bridge” is part of the project “bridge – Berline Netzwerk für Bleiberecht”

The project “bridge – Berlin Network for the Right to Stay” is funded by the Federal Ministry of Labour and Social Affairs and the European Union through the European Social Fund Plus (ESF Plus) as part of the programme “WIR – Networks Integrate Refugees into the Regional Labour Market” and co-funded by the state of Berlin (Berliner Landesmittel).

[1] Integration is a loaded word: for some, it implies a need for the ‘newcomer’ to adjust, without keeping in mind the fact that it is a two-way street between these ‘newcomers’ and the host country.

This article was produced as part of The Newsroom 27 competition, organised by Slate.fr with the financial support of the European Union. The article reflects the views of the author and the European Commission cannot be held responsible for its content or use.

This article was produced as part of The Newsroom 27 competition, organised by Slate.fr with the financial support of the European Union. The article reflects the views of the author and the European Commission cannot be held responsible for its content or use.