In Portugal, inmates introduced to opera to prevent recidivism

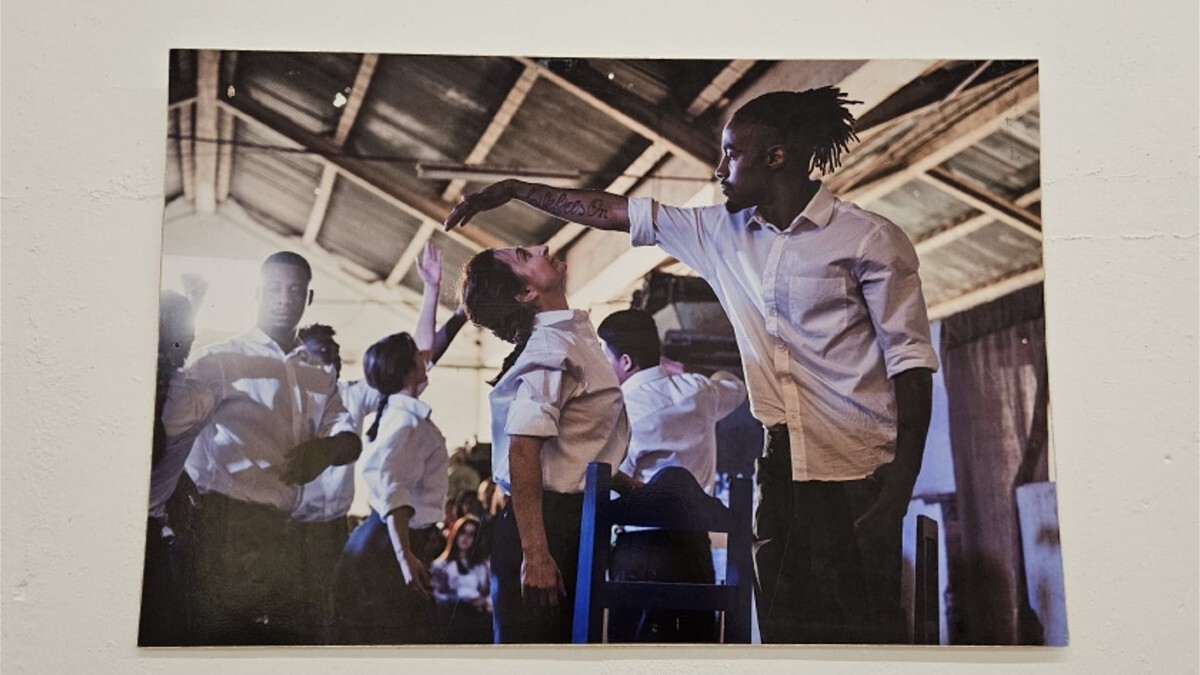

In the Leiria youth prison, the “Opera in Prison” project introduces inmates to art and music to help them reintegrate into society.

Criminal recidivism is a persistent problem in many countries. In many cases, people who have served their sentences and been released end up back in the prison system. In Europe, the rate can vary from 21% to 63%, depending on the country and the method of measurement, according to statistics from the World Population Review website.

To face this structural problem, numerous studies have highlighted the benefits of music. Hence the creation of “Opera in Prison”, run by the Musical Artistic Society of Pousos (SAMP) at the Leiria youth prison in Portugal, which houses inmates aged 16 to 21. This “school-prison”, created with the aim of promoting the re-education and social reintegration of young people to prevent them falling back into the prison system, is the only one of its kind in the country.

Staging opera performances in prisons: the idea may seem original, even utopian. However, the work carried out by SAMP since 2004 demonstrates that it is not only feasible, but also virtuous for the inmates, who still feel the impact long after the applause has stopped and the curtain has come down.

João (fictitious name), one of the participants, has been in the project since 2019. “I used to beatbox on the street, but when I came here and saw microphones, speakers, I liked it,” he reveals. Over the years, he has participated in different performances, highlighting the emotion of seeing his own image printed on a project’s shirt, which brought pride to his family and a sense of belonging. “It’s a good experience. I’ve evolved a lot, I’ve learned a lot too.” He describes how the project helped him overcome shyness, develop communication skills, and gain confidence. “It helped me to value small things.”

Pedro and Rui (fictitious names) joined the project with different motivations. Pedro uses his time in prison to complete remotely the Music and Digital course at the Leiria Polytechnic Institute. He joined “Opera in prison” as an intern, to seize the opportunity to live the professional experience necessary to obtain his diploma while incarcerated. There, he develops technical skills through opera. “It helps me grow as a professional, as a sound technician, gain communication skills, and work in a group.” For Pedro, the project also increased self-confidence. He highlights the transformation of the room, the Mozart Pavilion, into an auditorium, a change that made him feel like he was “in a real theatre.”

Rui joined a year ago and gradually became interested. It gave him the opportunity to fulfil the “dream of singing on stage.” “I sang with my sister on stage, and it was a more emotional, intense moment. I felt a lot of gratitude.” He emphasises the importance of the project in learning to communicate, gaining self-confidence, and respecting the different cultures present in prison. “Having to learn to deal with other people who don’t have the same personality as us that helps us a lot outside.”

Impulse control

Promoting education, vocational training, and access to job opportunities are fundamental in preventing recidivism and aiding in the reintegration of young people into society. It is in this sense that the project uses opera as a rehabilitation tool. David Ramy, a member of SAMP and project coordinator on the ground, visits the prison twice a week, with a palpable passion for the work and without prejudice, bringing the freedom to sing along. He works directly with inmates through musical training but also “with their families. This project is 40% here and 60% in Amadora, in Sintra, where they are from, most are from the neighbourhoods,” explains David. He asserts that opera teaches “impulse control.” Over three years of the project, participants learn to sing, control impulses, and think before acting.

“The key figure of the project is the hands of the conductor. A conductor teaches singing and to breathe before the note. To think about the right note you’re going to sing. You don’t sing when you want. You breathe, think about the note, and then emit the sound. That’s called impulse control. We start from the assumption that 95% of boys between 16 and 23 years old who are in here must not have known how to control their impulses. They spend 3 years doing an exercise, controlling impulses twice a week. Then, in an unpleasant situation, before singing the note, they think, control the impulse.”

According to David, SAMP tries to bridge the gap between inmates after release and job offers related to music. “We start by being the source. Music comes from here, dance, I bring you here a singer, a painter, a director, and at one point we become a bridge. We work with many orchestras and teachers. It’s a network of contacts that helps them.” Participation in the project is voluntary. Joel Henriques, coordinator of prison education and training within the prison, has been involved in the project since 2016, describing it as “very enriching for both the prison community and the young people who are part of the project. They begin to understand that they have some gains, not only internally, from their skills, but also from society that can see them differently.”

Rehearsals and performances take place in the Mozart Pavilion. The prison building was rehabilitated through funding from the European Union/POISE under the Portugal Social Innovation program in 2021. The rehearsal/performance room has now a stage, chairs, computer, and various instruments such as drums, piano, and guitar.

“This pavilion was completely destroyed. And it was built with that money. The project always appreciates the financial contribution of the European Union”, but “when a person or a collective is determined to make a project happen, it happens one way or another, regardless of the financing issues”. According to the coordinator, the project also has long-term sustainability because “what was needed in terms of materials and space we already have it. The rest is the human level, it’s us.”

It is in the Mozart Pavilion that a new Opera group is now being formed to start preparing for another show. Over 3 years, they learn singing techniques, breathing, theatre, and sound and light assembly. In previous years, the project has already performed on various stages including the Grand Auditorium of the Calouste Gulbenkian Foundation in Lisbon. 40 young people presented a staging of Mozart’s opera “Così fan tutte” to a moved and enthusiastic audience.

According to David the project’s approach is centered on trust and creating an environment of equality, where everyone, from participants to teachers, is on the same level. Progress is evaluated by performance in opera, behavioural changes, and attitudes towards music and life outside of prison. Although it was not possible to contact former inmates who participated in the project, David recounts how some remain connected to music and tell him how important it was for their reintegration into society. One such case is Diogo, who after release “found work as one of the chief technicians of the Gulbenkian Foundation.”

Impact on Reintegration

Joel highlights the changes he observes in the participants. They learn “to work in a team, one of the deficits they often present,” and to gain “self-control because they have several sessions and must respect the guidelines. During the performances, they transform themselves and seem much more committed. They learn that they are capable of taking actions that do not endanger others. They gain this notion that they can assume a role outside with confidence, self-esteem and respect for others. These are conditions that allow these young people to go out there without committing crimes again and have healthier relationships with others.” Joel also adds that “in here, they are constantly being watched and controlled, but they have this space, this project, where they feel free.”

For Joel, the artistic experience facilitates their reintegration into society. “I don’t think this resonates with everyone, but there are some in whom the seed of skills, knowing how to behave, how to listen, having to work to achieve a goal, remains. Especially in the big shows, this experience will mark them and they can transpose it to other aspects of life, in the relational field and work field. And I know of some cases that speak to me when they are already outside, and it is noticeable that there has been growth.” According to Joel, the internal skills they acquire are useful outside the prison to “know how to communicate.”

António (fictional name) also says that the project helped him find a new perspective in life. In his two years in the project he had the opportunity to participate in performances inside and outside the prison that allowed him to be with his family. He shared the emotion of having family members present at the performance at the Calouste Gulbenkian Foundation. “I saw the emotion of my mother, my brother. Seeing that I am trying to change. It gives us a chance let them know that we are changing and not continuing in the same life. I feel free here in the opera.” António says that of all he learned from music, what will be most useful to him outside the bars is “respect for others.”

The stigmatization faced by ex-inmates is a key factor contributing to the recidivism rate among young people. And it is here that performances inside and outside the prison can make a difference. If at first António saw the project as a way to pass the time, later herealized how it helps to change how he sees himself and how is seen by society because people watch the show “without prejudice” and understand that “prison also has this side of helping people, trying to put them on the right path. They can see social reintegration here.” According to David, music helps “change lives for the better. It changes the society that enters this prison.” The coordinator says that opera and performances help to deconstruct stereotypes and rebuild the relationship between inmates and families who had “lost faith.”

Joel also recognizes the importance of performances in society because “the reception was surprising. (The audience) was not expecting these young people, who are often labeled with deviant behaviours, to have these performances on stage and do what they did.” He also believes that it allows for a better relationship between inmates and “especially the surveillance agents who exercise more control over them. Through music, they have another perspective on things, they can see the other person’s point of view and be more empathetic.” David also noticed this evolution, “the way they relate to the guard is not the same. When he comes here in the first week and says ‘session over, everyone out,’ the way they react is not the same as in the last year. They breathe, control the impulse, joke, ask for one more minute. It’s completely different.”

Opera Challenges

However “Opera in Prison” also has its limitations. Insufficient rehabilitation programs and lack of support in social reintegration are two factors of criminal recidivism that neither music nor the project have been able to overcome. According to David, the biggest limitation is the lack of follow-up after leaving prison: “We should be able to have a project that continues. That we could fit into the difficulty of life. When these people are released, they don’t have time. The time they have is to find a job, money, girlfriend, house, car, to arrange the future. But we should have time for them to find a social project supervised by us.”

Another problem is the lack of follow-up from the prison. Joel says that there is no data on the true rate of criminal recidivism: “We actually do not have this data in terms of accuracy, but considering their age, if they commit another crime, they do not come to this prison because they are considered adults. I know there are repeat offenders who do not return to this prison.” In the case of those who participated in the project and have already been released, “there was none who had returned.” The prison also loses contact with inmates after release: “If they leave on parole, they remain connected to the system. We contact them, their family, and the technicians who accompany them outside. If they are released unconditionally, it’s only by their will.”

Joel acknowledges that lack of resources and internal limitations sometimes prevent sessions from taking place. Another obstacle is the limited time available for rehearsals, given the restrictions of prison life. Each rehearsal lasts only two hours twice a week.

Solution Exchange

The main conclusions that David draws “there are practices cross-cutting. Teaching breathing and self-control. Permeability, multiculturalism always starting from their work and co-creating with them”.

However “prisons need to have more opening time for these young men to be trained. It has to become more of a tool for change and less of a control tool. We have to risk having them closer to their families. We have to control that they don’t pass from one hand to the other like an object. Open up a range for inmates to spend more time outside the cells in activities.”

Despite not knowing the exact rate of criminal recidivism, it is certain that none of the released boys who participated in the project returned to the Leiria juvenile prison. Maybe the opera won’t end criminal recidivism 100%, but might have a contribution.

This article was produced as part of The Newsroom 27 competition, organised by Slate.fr with the financial support of the European Union. The article reflects the views of the author and the European Commission cannot be held responsible for its content or use.

This article was produced as part of The Newsroom 27 competition, organised by Slate.fr with the financial support of the European Union. The article reflects the views of the author and the European Commission cannot be held responsible for its content or use.