Saving the Lake of Constance

Shared by Austria, Germany and Switzerland, the Lake of Constance is the economic and natural heart of an entire region. But climate change is threatening its fragile ecosystem. A landmark research project is trying to map these changes to understand what is happening – and how to protect the lake.

On a freezing April afternoon, Franz Blum swiftly steers his small boat into the open waters of the Lake of Constance. Shared between Austria, Germany and Switzerland, it is one of the biggest lakes in the EU.

As the Austrian fisherman pulls one of his nets out of the water, there is one singular fish. It’s a Schleie, a type of fish that he catches not that often and from which he can’t make a living.

He carefully puts it in an enclosed space of the bay, to come back and collect it later when he has enough fish to fill up his cart.

“Back in the day, fifteen, twenty years ago, I needed a tractor to transport all my fish back”, he says. “Today, a little golf cart is enough.”

The Lake of Constance has been a key part of the region’s economy for centuries. Normally, it features a rich diversity in fish, birds and other wildlife, and in the summer, tourists flock to its shores and bathing stations.

But for the past decade, the lake has been changing drastically. Its fragile ecosystem has tipped out of balance. Some consequences are already visible, such as the crashing population of the native whitefish Felchen, one of the most important fish species for the regional fishing industry.

Why these changes are happening and what can be done to protect the lake and the livelihoods connected to it, led to the birth of a new research project, called “Seewandel”.

The threat of invasive species

“Seewandel” – literally meaning “changing lake” – has been mapping out the changes happening in and at the lake for the past six years. Funded by the European Regional Development Fund and the federal states of the three countries around the lake, the project has seen unprecedented scientific cross-border collaboration among seven regional research institutes.

“In the research community, there had been efforts to study certain aspects of the lake, for example invasive species”, says Piet Spaak, specialist for aquatic ecology at Eawag, the Swiss federal research institute for water technologies and science. He has spearheaded the project since its start.

“But we realized around 2016-17 that we needed a more integrated approach, since we were witnessing more and more effects of climate change and since these different topics are often interconnected”, he says, sitting in his office.

With sufficient funding found for the ambitious project, “Seewandel” officially took off in 2018.

The research work surrounding the Lake of Constance was divided up into sub-projects, which the different institutes in Austria, Germany and Switzerland focused on depending on their specialties.

One topic demanded particular attention from the scientists: invasive species were wreaking havoc in the lake’s biological composition. One of them is a tiny mussel, called the Quagga mussel.

“The Quagga mussel does a lot of damage”, explains Spaak. This tiny species filters the water of the lake for algae and plankton, its main food sources. While this process clears up the water and can make the lake visually more attractive, for example for swimmers, it creates a problem: the mussel is so efficient at filtering the water that it actually takes away these food sources from other species, such as fish. Although the Lake of Constance as a so-called alpine lake has a relatively low concentration of nutrients by nature, the impact of the quagga mussel is so drastic that it can endanger the survival of other wildlife.

And the problem doesn’t end there: the mussel, being a non-native species, gets transferred to lakes through human activity – and once it is inside a lake, it is impossible to get rid of it.

Today, in some parts of the Lake of Constance, there are about 20 000 mussels per square meter, and they multiply at astronomical rates every year.

Research findings of “Seewandel” have shown that the only possible measure against the mussel at the Lake of Constance is prevention, such as cleaning boats and fishing gear before they get transferred to another body of water. That way, the mussel doesn’t remain attached to them.

Nearby lakes, such as the Lake of Zurich, are currently still free from the mussel. But this could change quickly.

“The problem is that there is no control, as all of these measures are currently voluntary. I wish of course that there would be more action on this”, says Spaak.

Concrete measures would however need to come from the regional governance and political structures, among which are the three countries, but also institutions like a fishery commission and the IBK, the International Conference of the Lake of Constance.

Karlheinz Diethelm is at the helm of the IBK’s commission for the environment. He points out the importance of communicating the findings of research like “Seewandel” to the political sphere and the broader public in order to achieve a real impact.

„The environment commission has made it one of its key objectives last year to encourage dialogue between science and the fishermen“, he says.

An uncertain future for the Felchen – and the lake

The Quagga mussel is only one part of the destruction caused by invasive species at the lake. The Stickleback, a fish species, hunts plankton and the offspring of other fish. The larvae of the Felchen are a particularly easy prey. It has had a much more significant effect on their population than the Quagga mussel, as it has been present in the lake for much longer, according to the researchers.

And the Stickleback’s impact on the Felchen endangers the livelihoods of people like Franz Blum.

“I’m the last and the youngest fisherman working full-time on the Austrian side of the lake today. The others are either just about to retire or are working a side job, since fishing got too difficult”, says Blum as he steers his boat, doing his best to keep the course against the biting wind and the waves.

The situation that fishermen like Franz Blum have been observing and living is confirmed scientifically by Alexander Brinker. He has been leading research into the fishing situation as part of “Seewandel”, at the Fisheries research institute in Langenargen, on the German side of the lake.

Aside from the crashing Felchen population due to a lack of food and the havoc wreaked by the invasive species, he also points out the problem of water temperature changes as the lake heats up due to climate change.

“For one native fish species, the Trüsche, the lake has already become too warm. Its eggs can only survive if the water temperature remains below 5 degrees Celsius”, Brinker says.

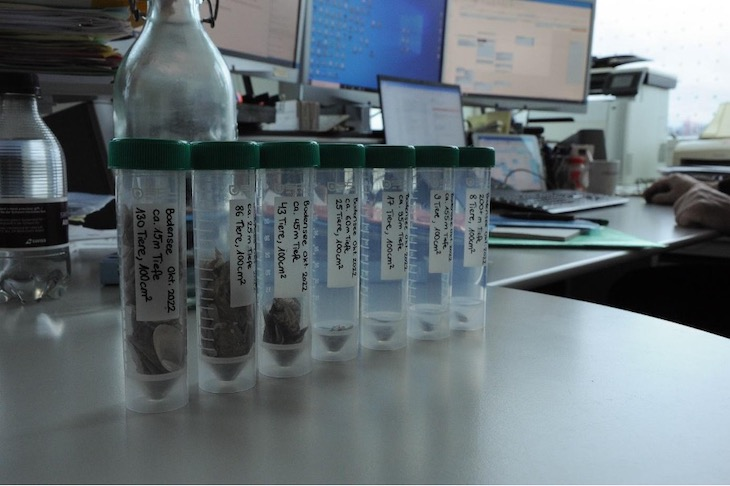

The scientists have started to make the eggs hatch outside of the lake in breeding stations like in Langenargen, before releasing the small fish back into the lake. It’s the only way this fish species will continue to live in the Lake of Constance for now.

“What we have also noticed is that the water temperature might also become a problem for the Felchen. We think that the Felchen might be struggling to put on the necessary weight in summer. This is because the plankton they eat is present in the surface water, which however gets too warm for the Felchen. So, they might hunger despite having food available.”

Although this remains a hypothesis the researchers still need to prove, they do know that the Felchen are not in good shape. It’s why, partly due to the research done during “Seewandel”, a three years-long ban on catching Felchen has been decided by the regional governance structures.

This measure is meant to give the population time to recover – at least that is what researchers are hoping for.

The first results of the project have also shone the light on remaining gaps in the research; it’s why a continuation of “Seewandel” has been approved until 2027 to focus in more depth on the modelisation of climate change consequences for the lake. The researchers in the teams led by Piet Spaak hope that some of the existing models of changes in the lake that their project has already produced, together with the future ones, could eventually be adapted to research on other lakes in Europe. This could help measure drastic changes in their biological compositions or water temperature, and inform preventative or adaptive measures taken by local governance structures.

Meanwhile, for the ecosystem of the Lake of Constance, the changes are already significant, and the outlook is uncertain, just as much as for the fishermen like Franz Blum.

“I don’t need to catch the masses of fish I used to catch; I just want to be able to continue my work. But I can’t do it if it’s just to survive day by day”, he says, looking out towards the lake one last time before returning home for the day.

This article was produced as part of The Newsroom 27 competition, organised by Slate.fr with the financial support of the European Union. The article reflects the views of the author and the European Commission cannot be held responsible for its content or use.

This article was produced as part of The Newsroom 27 competition, organised by Slate.fr with the financial support of the European Union. The article reflects the views of the author and the European Commission cannot be held responsible for its content or use.