An ambitious underwater tunnel in the Baltic Sea to boost the economy of two islands

In the Baltic Sea, a gigantic road and rail project promises to facilitate trade between the two countries. For the inhabitants of the two islands to be linked by the future tunnel, this new infrastructure could reverse the trend of economic decline.

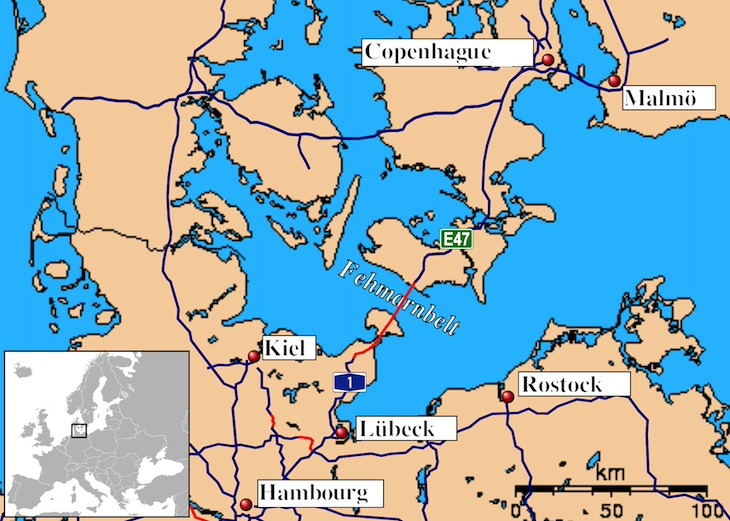

In 2021, an extraordinary project began in the Baltic Sea: the construction of an underwater tunnel which, once inaugurated – in 2029 if all goes well – will be the longest in the world, stretching over 18 kilometres. The aim is to create a new rail and road link between Denmark and Germany, reducing the journey time by train between Hamburg and Copenhagen from four and a half hours to two and a half.

The aim is also – and perhaps above all – to revitalise two European islands, Lolland in Denmark and Fehmarn in Germany. With a budget of €8 billion and a timetable spanning thirty years, this ambitious project has significant implications for local communities, but is not without its share of environmental concerns.

While Denmark is providing most of the funding for the project, the European Union (EU) is contributing €1.1 billion. The cross-border region, known as Fehmarnbelt, has also been considered a Euroregion since 2006, which implies structured cooperation between local authorities supported by the EU’s Interreg programme.

This EU initiative has not only facilitated cross-border traffic, but also led to the construction of the tunnel being brought forward to ensure that it adds real value to regional development. For the inhabitants of these islands, the tunnel represents much more than a simple infrastructure: it is a real lifeline for their declining rural economies.

Anders Wede, a 40-something years old engineer, whose family has roots in Rødbyhavn, sees the project as a way to restore his hometown to its former glory. The town, once vibrant, now features a main street lined with “For Sale” signs, symbolizing its decline. For him, the project is personal; he will rebuild his community.

Puttgarden on the German island of Femern, are facing another problem. A fall in its young demographic. In 2021, the 0-29 age group made up only about 24 percent or roughly 3,100, of the entire island population of around 13,000.

Lasse Stiehr, at 26, therefore represents a shrinking demographic of young residents on the island. He is hopeful that the tunnel will not only stem the tide of youth migration but also enhance the island’s connectivity, making commuting to larger cities like Copenhagen more feasible.

The fabric of our society

As Europe grapples with urbanization, the tunnel could potentially reverse the fortunes of their communities, offering new opportunities for growth and sustainability. It’s a reminder that infrastructure projects like the Femern Connection play a critical role not just in facilitating movement but in shaping the economic and cultural landscapes of the regions they serve. As Ursula von der Leyen, President of the European Commission, points out, rural areas form the “fabric of our society,” underscoring the importance of such developments in maintaining the vitality of these regions.

A 2021 communique from the European Commission highlighted that while 80% of the Union’s territories are rural, only 30% of the population resides in these areas. Von der Leyen has pointed out the severe consequences this imbalance could bring, such as declining employment and increased migration of youth from these regions.

We hardly consider the infrastructure that surrounds us — similar to how we seldom think about our blood circulating or breathing. In today’s hyper globalized world, we don’t fully appreciate how crucial roads, trains, and tunnels are to our societies. Culture and economy seamlessly flow across borders, helped along by these physical infrastructures. In an era of increasing urbanization in Europe, Ursula von der Leyen warns that we risk losing what she refers to as “the heartbeat of our economy”. The rural areas.

For a vivid example of the issues von der Leyen describes, one needs only look at the two Danish and German islands.

Regaining dynamism

In Rødbyhavn, Anders Wede enters the cafeteria. As he queues for lasagna, he greets a woman at another table. “I went to high school with Marianne. There are many from my elementary and high school days here,” he comments as he sits down. For Wede and many who have grown up in Rødbyhavn, working on the Femern project holds a special significance. Wede’s parents still live in the town, and his sister was even confirmed at the hotel on the harbor, which now serves as offices for the project staff.

Yet, Rødbyhavn is not the same town Wede grew up in. The abandoned main street, with “For Sale” signs in almost every window, serves as a painful reminder of a town well past its prime. For him, there are many reasons he’s involved in the project, but one stands out: “When you have watched your own house and town decay, you want to rebuild it to what you remember.” Wede hopes to show his children the town as he remembers it.

Meanwhile, in Puttgarden, Lasse Stiehr stands at the harbor, waiting for a truck delivering parts for the construction which is well underway on the German side of the Femern connection.

Arriving on Femern by ferry from Rødbyhavn, visitors are greeted by vibrant yellow rapeseed fields and the calls of seagulls that have followed the ferry since it departed Rødbyhavn. Having grown up and still residing on Femern, Stiehr has witnessed the development firsthand, making it even more special to now work on the project.

“As a local, I have always been interested in the development of the project. I am deeply convinced that the entire region will benefit from it. But the best part is that it’s right on my doorstep.”

For the future

Anders Wede sets down his plate in the hotel cafeteria in Rødbyhavn. Lasagna and salad are on the menu today.

“Rødbyhavn will not end up as a pass-through town,” he states proudly. He believes the tunnel will create opportunities for the small town and Lolland municipality long after the project is completed. However, he also notes that it’s crucial for politicians to act while there’s still time to harness these benefits for the community. “It’s everyone’s hope that the politicians will strike while the iron is hot.”

According to Wede, it’s essential to initiate projects that engage the workforce already in Lolland. By doing so, many people will stay in the municipality, attracting more investors.

For Stiehr, the problem, and the solution, are different. He sees the tunnel opening the possibility for more young people to consider settling on Femern. The tunnel will make it easier for them to commute to Copenhagen and find employment there. He believes that this will significantly change Femern. Young people will see the appeal in living in the countryside but working in Copenhagen or another nearby major city, closer than Hamburg.

For the 26-year-old German, the reason for working on the project is clear:

“I’m proud to be part of it. To be able to tell people in the future, it wasn’t always like this. You could drive to Denmark in ten minutes. We made that possible.”

This article was produced as part of The Newsroom 27 competition, organised by Slate.fr with the financial support of the European Union. The article reflects the views of the author and the European Commission cannot be held responsible for its content or use.

This article was produced as part of The Newsroom 27 competition, organised by Slate.fr with the financial support of the European Union. The article reflects the views of the author and the European Commission cannot be held responsible for its content or use.