To counter brain drain, the European High North is banking on video games

In Sweden and Finland, the Borderless Game Academy is developing a cross-border curriculum. The ambition, beyond providing training for video game professions, is to diversify the local economy by creating new industries.

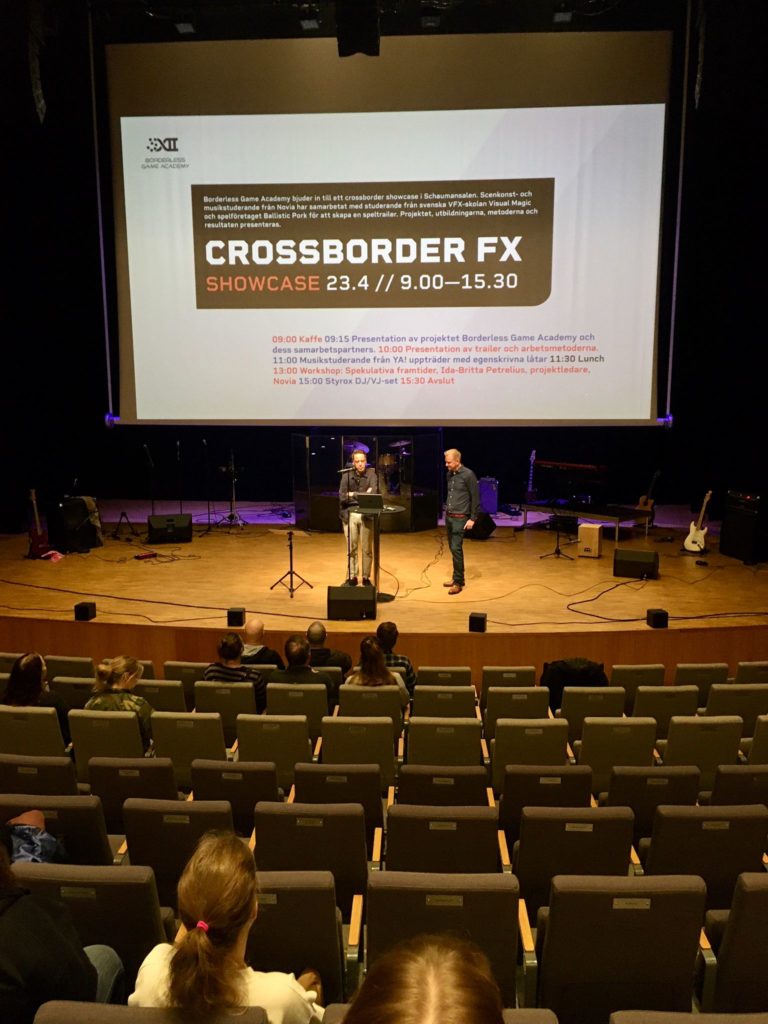

“The year is 2124. When you imagine the future, what does it look like? Is it a dystopia or a utopia? What groups are there and what is their driving force?” Ida-Britta Petrelius, project manager at Novia University of Applied Science (Novia UAS), challenged Borderless Game Academy students to envision video game design through the lens of sustainable development, using pop culture as a catalyst for societal change. This workshop was part of a transnational showcase held in Pietarsaari last April to spotlight the Academy’s early successes, launched last September with Interreg Aurora’s backing.

On both sides of the Gulf of Bothnia, building bridges across borders is second nature, and Europe’s influence is tangible—even if one is closer to the Arctic Circle than to Brussels. “Northern Sweden is very close to Northern Finland, so it’s more natural to cooperate with them than with Stockholm,” explains Johan Linder, founder and head of Visual Magic Education. Tobias Björkskog, project manager at Novia UAS, echoes this sentiment, noting that such collaboration with Skellefteå has been ongoing “for a long time.”

An ambitious cross-border cooperation project

The launch of the Borderless Game Academy was driven by contemporary considerations. The creative industries, particularly the video game industry, are developing at a rapid pace in northern Europe, in a context marked by the need to diversify the local economy. While this strong growth is opening up new employment opportunities, it also creates more specialised training requirements, such as in the field of video game design. Even in Europe’s most northern parts, there is a shortage of skilled labour due to low population density combined with a strong brain drain among young people.

That is why the ambition of the Borderless Game Academy is to create a stimulating educational environment so that students no longer need to leave the region to study elsewhere. While study programs already exist on both sides of the border, the challenge is to strengthen the links between the Finnish and Swedish education systems in order to create a truly integrated cross-border curriculum.

“The idea is to find a model that combines the Swedish and Finnish school systems, enabling students to begin their studies in Sweden and then continue them in Finland, in order to obtain a diploma recognized in both countries,” explains Tobias Björkskog.

Overcoming challenges

This is a major challenge, given the differences in approach and content offered by Visual Magic Education and Novia UAS. In Sweden, video game design education is provided by a specialised school focusing on technical skills such as the creation of digital visual effects.

At the end of the two-and-a-half-year course, students obtain a qualified professional diploma. In Finland, this training is provided at university, with a Bachelor’s degree awarded after three years of study. The approach focuses more on the performing arts and music, but also on entrepreneurship and the management of cultural projects.

Against this backdrop, merging these two higher education systems is as much an administrative feat as it is a legal one, especially considering that education is not a shared competence of the EU Member States.

Europe as a catalyst for change

Launched last September, the Borderless Academy project is financially supported by the European agency Interreg Aurora, whose role is to strengthen cross-border cooperation, with sustainable development as a common thread. For the Borderless Game Academy, the funds allocated by Interreg Aurora amount to €411,235 over a two-year period, almost two-thirds of the total budget of €632,669.

Despite the financial support of the municipality of Skellefteå in Sweden and the region of Lapland in Finland, such an ambitious project would not be possible without European funding. This support is all the more important because, in addition to their different approaches and working methods, there is a major difference between Novia UAS and Visual Magic Education: while the former is the largest Swedish-speaking university in Finland, with 5,000 students, the latter has just 60.

For Johan Linder, however, this is not a problem, quite the contrary: “We face the same challenges, because it’s difficult to develop creative industries, not to mention the fact that developing this type of cross-border training is not without financial risk. We are finding ways of complementing each other.”

Laying the foundations for long-term impact

For the time being, the project is focusing on four areas of work, which are intended to lay the foundations for the future development of the Borderless Game Academy: Firstly, the aim is to design a coherent transnational study program, and then to develop lasting cross-border alliances between higher education institutions on both sides of the border. At the same time, the idea is to stimulate collaboration between students via joint study projects and meeting opportunities, in order to instil a synergy between video game training institutes and the student body.

Six months into the project, the organisers of the showcase at Pietarsaari are satisfied and confident about its success, noting that “although this partnership has only existed for a short time, it is already bearing fruit.”

It remains to be seen whether the expected results will be achieved by the end of August 2025, when the Interreg Aurora funding comes to an end. Anna-Maria Ruisniemi, the program’s communications manager, is optimistic: “The support from Interreg Aurora is indispensable to create a platform for developing this cross-border collaboration with combining competences from two countries. If they’re successful, their model could be exported to other areas.”

Culture as a driver of change

On the other side of the Gulf of Bothnia, in Skellefteå, Tim Leinert is following the beginnings of the Borderless Game Academy with great interest. The young man is in charge of business development at Arctic Game, a hub launched in 2015 with the aim of federating the video game and e-sport industry ecosystem in northern Sweden. His work is to build a basic infrastructure, create a community, but also to support business and innovation, because for him, “the creative industries are small, but important for creating the industries of the future.”

Here again, Europe is never far away, and for Daniel Wilén, the head of the hub, the conclusion is clear: “The development of the Arctic Game would be impossible without the support of the EU.” Despite a business model that has yet to sustain itself, after nearly 10 years in operation the results are visible: Arctic Game has 70 companies and 17 training courses, spread across four towns, with a total of 500 employees.

It is also the fastest-growing cluster in the video games and e-sports sector in Northern Europe. Tim Leinert goes as far as talking about “a grassroots movement, based on community spirit and the desire to create lasting change within the city.”

Skellefteå: A city reinvented

To understand how the video game industry came to be established in Skellefteå, we need to take a step back in time. In fact, this town, which is sometimes referred to as the “city of gold,” is undergoing a major transformation. For a long time, it was the epitome of an industrial town, hosting one of the richest mineral deposits in the world, as well as the headquarters of Skellefteå Kraft, Sweden’s second largest electricity company after Vattenfall, and since 2017, the site of Northvolt’s first battery factory.

As early as the 1980s, Skellefteå was one of the very first municipalities in Sweden to invest in a supercomputer, which enabled it to position itself as one of the country’s leading cities in the field of information technology. Later, in the 1990s, video game training programs were launched, but students were forced to leave the municipality and move to Stockholm, as there were no video game companies or studios.

“There was no tradition in the video games sector, we were starting from scratch, and we had to create a lot of activity,” explains Jannike Lindbergh, a business development manager at the municipality of Skellefteå, who specialises in the video game sector.

One of the pioneers in this field is Daniel Wallström, who humorously notes that when he started out in the industry in 1997, video games were still sold in CD-Rom format. He is now director of Spinoff Games, a studio that launched the mobile video game “Disc Golf Valley” in 2021, a game that quickly became a popular success, with two million downloads and 130,000 monthly users, making it one of the most striking “made in Skellefteå” success stories of recent years.

Despite this performance, Daniel Wallström remains modest, aware of the difficulties the video game industry faces: “It’s an industry that depends on ideas, luck, and timing, and it’s difficult to predict what’s going to happen. The market is saturated, so even if you have a good game, there’s no guarantee of success.” Daniel Wilén also acknowledges that “the ecosystem is fragile” because of the difficulty of raising capital at the moment.

This is why, in his view, early support for local businesses is decisive “to work intelligently” and thus optimise growth processes, because “you have to find what works straight away.”

An industry in the shadow of Northvolt

Another of Skellefteå’s gaming industry veterans is Pär Hultgren, who runs Gold Town Games, a studio specialising in the development of mobile games around sports management, which has even been listed on the Swedish stock exchange since July 2016. When asked about his vision of the local ecosystem, this native of the country, who compares Skellefteå to Pittsburgh, makes it clear from the outset that he takes a post-colonial perspective, considering that “Northern Sweden has always been a colony, a stolen land.” He adds that “the problem is not the European Union, but the Swedish government, because Sweden does not want to devote resources to the northernmost regions.”

He cites the example of Arrowhead Game, an independent studio launched in 2008 by a group of students based in Skellefteå, which was soon forced to relocate to Stockholm in the early 2010s, where it finally broke through with games such as Magicka, which enjoyed worldwide success with 1.3 million copies sold when it was released in 2012. When he doesn’t speculate on how Skellefteå would have developed if Arrowhead Game had stayed local, he is also concerned about the influence of the giant Northvolt, which risks changing the city’s identity in the long term: “If we lose the creative industries, it will be difficult to maintain the service economy, and we will become a production city like Kiruna.” In his view, this is above all a political issue, at both local and national level, because “the Swedish government wants it that way.” Jannike Lindbergh nuances this view, stressing that the development of the video game industry is “a very important project for the municipality.”

The rising generation changes the game

The future of Skellefteå may actually lie in Jörn, a small town 55 km from the municipality. This peaceful village of 600 people, most of them retired, is becoming the new Eldorado for young video game creators, even attracting study visits from abroad. The Game Village, as it is called, has it all: launched jointly by Arrowhead and Mind Detonator studios in 2022, this incubator, housed in a former community centre, offers five studios the chance to devote themselves 100% to video game development with complete peace of mind.

Another advantage is that, thanks to a partnership with Arctic Game, these studios benefit from support in the search for funding, training in commercial development and contract negotiation, as well as administration. In the short term, the idea is to create fair working conditions to ensure decent wages for creators, whose working conditions are often precarious; in the long term, the aim is to develop sustainable economic models, enabling them to become majority owners of their studio, and thus keep control of their business.

One of these young talents is Harry Heath, a young Briton who took the plunge just over a year ago, moving from Stockholm to Jörn. He is now one of the twenty or so designers working in the Game Village, and runs the Cold Sector studio, which is preparing to launch its first title, “An Island Away.” He has nothing but praise for the concept: “Here, I can create what I like, because it’s a small community of people who have a hand in everything.”

Community and collaboration are the keywords here, because the twenty or so designers who work in the Game Village spend almost all their lives together. In fact, they live in shared flats in typical Swedish villas all located on Storgatan, the main road that goes through Jörn, just a stone’s throw from the studios. Another designer based in Jörn is Therese Olofsson, who is an exception in several respects: firstly, she is one of the few women in this very male-dominated world; secondly, she is also one of the few women to have launched her own studio, Tricky Wispers, where she is currently developing “Blessed Curse.” Even so, she describes Game Village as “a friendly environment, one of the best places in the world to make video games.”

The secret behind Skellefteå’s success

Many factors explain the success of the “Skellefteå model,” but the strong connection within this ecosystem is undoubtedly one of the key factors at play: the flat hierarchy and absence of bureaucracy facilitate regular and intense contact between all the actors involved, which means that decisions can be taken and implemented more quickly. “We are used to cooperating, because our populations are small and far from the capital. As there are not enough resources in this area, we are forced to cooperate, and that is a strength,” explains Jannike Lindbergh.

For Tim Leinert, the human factor is also one of the undeniable keys to this adaptation process, because in Skellefteå, one “believes in people with big dreams.” Daniel Wilén couldn’t agree more and argues that “the industry creates a lot of value—not just economically. It creates a more diverse labour market, but also social diversity in the local communities.”

In this transition phase, the notion of impact at every level is also an important aspect given the tight financial resources at the moment. That is how developing games with “added social value” became a way to achieve more with less. A recent example of this approach is the video game “Fig,” which was developed in conjunction with video game designers, psychiatrists, and scientific experts. Inspired by behavioural therapies, this application provides patients suffering from depression with a playful guide on the road to recovery, and has already been successfully tested on 10,000 people, suggesting great potential if it is rolled out on a larger scale.

The Game Village in Jörn shares this vision of a committed industry serving the local population. The incubator regularly opens its doors to local residents to show them what goes on behind the scenes and explain how a studio works, thereby democratising the video game industry. Harry Heath is already looking ahead: “We’ve received so much, so it’s important to give back to the community. If we could, we’d open a café and a bar, to make this town a town again.”

In Skellefteå, the future will be European

The development of the video game industry in Skellefteå and Pietarsaari is currently taking place on two levels: local and European. Everyone seems to agree that European funding is not a long-term solution, and this transition must be sustainable if the video game industry is really to take root. That is why Tim Leinert is calling for a common vision at a local level, in order to strengthen collaboration between all the players involved in the local ecosystem, optimise existing resources, and diversify sources of revenue. “We can’t expect everything from the EU: the industry has to become self-sufficient and self-financing,” he comments.

In the long term, the goal is not to remain limited to the north of Sweden, which is why the cooperation with other hubs across Europe is becoming an increasingly important part of the Arctic Game’s work. Ultimately, the aim is to bring together the various European hubs to launch the first pan-European hub, in a context marked by competition from the United States. In this growing process of internationalisation, the commitment of the citizens of Skellefteå to serving the city remains intact, because they are determined to make things happen, and failure is not an option, as Tim Leinert explains: “We have to do it our way, and it’s going to take time, but it’s going to work.” Daniel Wilén goes even further, saying that “the Skellefteå model can be exported.”

This article was produced as part of The Newsroom 27 competition, organised by Slate.fr with the financial support of the European Union. The article reflects the views of the author and the European Commission cannot be held responsible for its content or use.

This article was produced as part of The Newsroom 27 competition, organised by Slate.fr with the financial support of the European Union. The article reflects the views of the author and the European Commission cannot be held responsible for its content or use.